Kansas City—10.27.2025

Raindrop Foundation

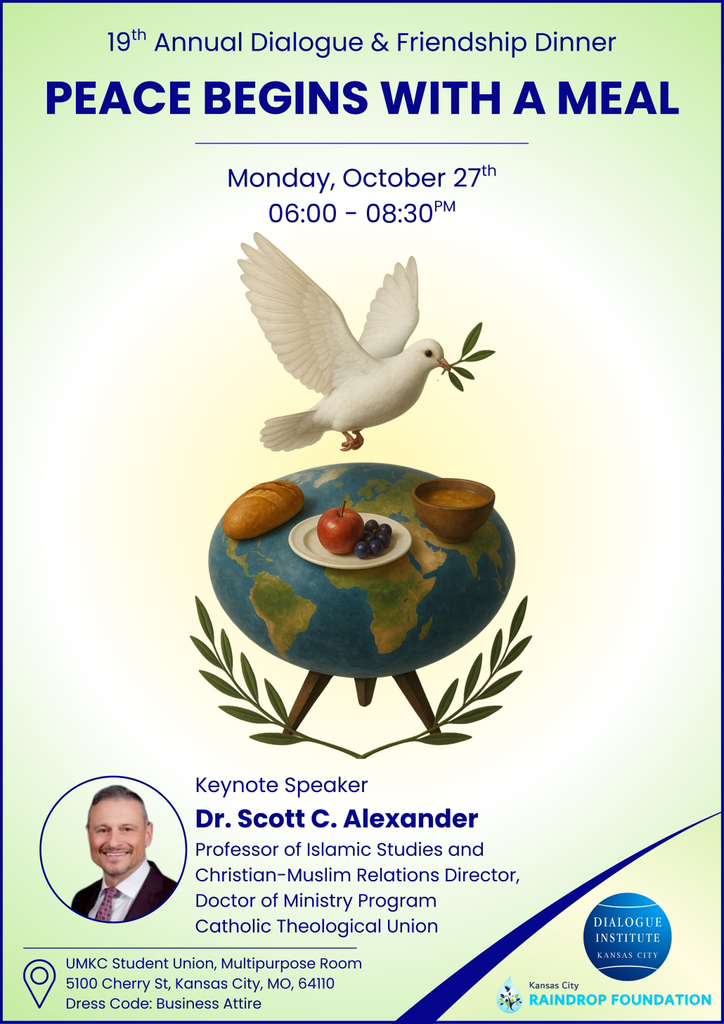

“Peace Begins with a Meal”

1. Introduction

A. Greetings of Peace

Taslim

Jewish

Namaste

Peace be with you!

B. Acknowledgment of Country

On behalf the Raindrop Foundation, I wish to acknowledge and honor the indigenous peoples who, for generations, have cared for the land on which we gather. I wish to recognize the suffering, nobility, and resilience of all the native communities in the region, including the the Kaw (Kanza), Osage, and Shawnee peoples as the ancestral stewards of this land, as well as to acknowledge that this land area is also home to other removed tribes now in Kansas and Missouri.

C. Gratitude

Man la yashkuru l-nas la yashkuru Allah.

Mr. Mehmet Unalan, Executive Director of the Raindrop Foundation

The great Enes Kanter Freedom

Prof. Ibrahim Keleş

Dr. Eyyup Esen

Mr. Turgay from Indonesia (who picked me up from the airport)

All the volunteers—the good women and men of the Raindrop Foundation

Finally, all of you gathered for this joyous event who could be doing so many other things with their valuable time—like watching the Chiefs play the Commanders—but who instead generously chose to be here this evening—at least before rushing home to catch the second half. LOL.

Cok, cok tesekkur ederim. Muchas gracias! Grazie mille! Thanks you all so very much!

D. Joke about the Man who orders two coffees.

E. The Spiritual Significance of Sharing a Beverage and Especially a Meal—a phenomenon anthropologists refer to as “Commensality”

It sounds so simple—maybe to some even simplistic—but it couldn’t be more true to say that “Peace begins with a meal.”

In fact, it’s no exaggeration to say that this title of our evening’s event is actually ancient spiritual wisdom deeply embedded

In the great spiritual traditions of the human family.

1. The Last Supper (Christianity)

Perhaps the most iconic sacred meal in Western tradition, the Last Supper symbolizes communion, unity, and forgiveness. Jesus gathered his disciples—including one who would betray him—around a shared table, transforming a Passover meal into a ritual of reconciliation with God and among humans. The Eucharist that emerged from this event remains a central Christian practice embodying peace, community, and divine hospitality.

⸻

2. The Jewish Shabbat and Passover Meals

In Judaism, the Shabbat dinner each Friday evening and the Passover Seder are powerful instruments of social cohesion. The rituals of blessing, storytelling, and shared food renew communal identity and transmit collective memory. The Seder in particular commemorates liberation from oppression and enjoins participants to imagine a world of justice and peace—reminding Jews that shared remembrance and hospitality are prerequisites for communal harmony.

⸻

3. Islamic Iftar during Ramadan

During the holy month of Ramadan, Muslims fast from dawn until sunset and then gather for iftar, the evening meal that breaks the fast. Traditionally, iftar begins with dates and water and is shared with family, friends, and often strangers or the poor. This act of communal eating breaks down social hierarchies, reinforces empathy, and fosters solidarity across the ummah (global Muslim community).

⸻

4. Indigenous Peacemaking Feasts

Many Indigenous cultures across North America and beyond have long used shared meals as central to peacemaking. For example, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) incorporated food-sharing ceremonies into treaty negotiations and reconciliation processes, understanding that one cannot make peace with someone with whom one has not broken bread. The act of eating together symbolized mutual trust and respect.

⸻

5. Buddhist Dana and Almsgiving Meals

In Buddhist communities, the practice of dana (generosity) often takes the form of offering food to monks. These offerings, and the shared meals that sometimes follow, cultivate interdependence, humility, and compassion—values essential to peace both within oneself and among others. Communal vegetarian meals in monasteries are often silent and mindful, fostering harmony and awareness of shared existence.

F. Pathetic Gesture or Antidote to “Stupidity”?

Given the enormity of human suffering in so many places around the globe and even here in the US where our differences and divisions see to be tearing at the fabric of our shared civic life, what can a meal possibly do? Some would argue that a meal such as as the one we are sharing tonight is a largely symbolic if not even pathetic gesture that does nothing to divert us from the path of self-destruction we seem to be determined to follow to the bitter end.

I would argue that a shared meal with those who are different than ourselves can be an important way of pushing back against what the great German Confessing Church Pastor, theologian, and martyr in resistance to Nazism—Dietrich Bonhoeffer—would likely diagnose as the deadliest malady facing US American society today…”Stupidity.”

In his meditation on the “stupidity” (Dummheit) that enabled the rise of Nazism and ultimately the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust of European Jewry, Dietrich Bonhoeffer warns that it constitutes a far greater danger to the common good than malice, for while evil can be confronted, exposed, and resisted, stupidity is impervious to reason and immune to facts. The “stupid” person, Bonhoeffer maintains, is not necessarily dull of mind, but one who, under certain social and historical pressures, relinquishes inner freedom and independent judgment, allowing themselves to be overtaken by slogans, clichés, and the sway of mass movements. In this sense, stupidity is less an intellectual defect than a sociological phenomenon, arising most acutely in times when political or religious power surges, demanding conformity and disabling autonomy. The danger lies not only in the stubbornness of the “stupid” but in their unknowing complicity: they become instruments capable of great harm without perceiving it as such, thereby more readily susceptible to manipulation and abuse. Against this, rational argument or moral appeal is futile; liberation, not instruction, is required. Yet Bonhoeffer insists this is not a counsel of despair. Stupidity is not a permanent condition, nor is it a universal judgment on “the people.” It is context-dependent and reversible, overcome only when external conditions allow for inner emancipation, ultimately rooted in the “fear of God” as the ground of true wisdom and responsibility. Thus, while stupidity undergirds some of the most destructive currents of public life, Bonhoeffer also points to the possibility of its overcoming through both societal and spiritual renewal.”

If you’re anything like me, if you are hearing these words of Bonhoeffer for the first time you may be thinking: “Yes! That is such an apt description of the condition that afflicts so many of THEM.

THEY are pitiable in THEIR lack of awareness of what has happened to THEM and how THEY are contributing to the destruction of US all.

This, my dear friends, is one of the more pernicious hidden dangers of stupidity—that we think it is THEIR malady and not OUR own as well.

Although the neurological and cognitive sciences teach us how natural and even automatic this response is—to compare the best of OUR in-group with the worst of THEIR out-group—this doesn’t make it any less dangerous.

If we, as people of faith, are to be agents of change for the common good in adherence to the guidance of divine wisdom and truth, then we must take care to repent from our own stupidity and seek the liberation from the forces of spiritual captivity of which Bonhoeffer so elegantly speaks.

But how do we do this?

G. The Practice of Hoşgörü

From the late 1950s and early 1960s during his earliest days as a humble imam and preacher in the mosques of Edirne and Izmir in his native Turkey, to the day he died in self-imposed exile in Saylorsburg, PA on October 20th of last year (2024), M. Fethullah Gülen (Hocaefendi) was a great Muslim scholar, spiritual teacher and inspiration behind the global educational, humanitarian relief, and intercultural dialogue, movement known as “Hizmet”—the Turkish version of the Arabic word for “service.”

In fact, for those of you who may not know this, Hizmet is the very movement that gave birth to the Raindrop Foundation and countless institutions like it in well over 150 countries around the world.

Among the many ideals Mr. Gulen emphasized as foundational to the life of any faithful Muslim—indeed any authentic human being—was the praxis of hoşgörü.

Defintion…

“Under the lens of hoşgörü the merits of believers attain new depths and extend to infinity; mistakes and faults become insignificant and whither away until they are so small that they can be placed into a thimble.”

H. Conclusion: The Shared Meal as Medium of Hoşgörü and Pathway to Peace

Across cultures and centuries, the simple act of sharing a meal has served as one of humanity’s most profound gestures of peace and belonging. Whether around the Passover table, the Christian Eucharist, or the Muslim iftar, the shared meal dissolves divisions and reaffirms our shared dependence on sustenance—and on one another. From Indigenous peace feasts to Sikh langar, communal dining has often functioned as a lived parable of equality, where strangers become kin and adversaries become neighbors. In so many of our faith traditions, eating together is not merely social custom but moral and spiritual practice: a sacred ritual of reconciliation that binds individuals into community, memory into hope, and hospitality into the architecture of peace itself. The shared meal is, in other words, a medium for the sacred practice of hoşgörü.

In fidelity to God, divine revelation, all the prophets and messengers, and in honor of the wali Allah, the “friend of God” Hocaefendi M. Fethullah Gulen—qaddasa Allah sirrahu—in these dark and dangerous times, I charge myself and humbly invite each and every one if you to make every effort to eschew all stupidity by asking God for the gift of hoşgörü so that, like God Godself, we always strive to see one another—especially those with whom we disagree most vehemently—through the eyes of compassion and grace.

Amin

Scott C. Alexander, Ph.D.

Professor of Islamic Studies & Christian-Muslim Relations

Director, Interschool Doctor of Ministry Program

scalexan@ctu.edu

t. +1 773.580.7239